When Rene Magritte was thirteen, his mother committed suicide by jumping into the River Sambre. She had made previous attempts at suicide in the past, which drove her husband to lock her into her bedroom. In the early morning of February 24, 1912, she found the key and escaped. It is said that when her body was dragged out of the river, her white nightgown had wrapped around her head. This made Magritte obsess for the rest of his life over the seen and unseen.

Unlike the other surrealists, Magritte’s personal behavior and affectations were unremarkable. He married his childhood sweetheart, was fairly reticent, blended into the crowd as a normal man in suit and bowler hat, and lived in suburban anonymity. His personality is a particularly strong counterpoint to the exhibitionism of Dalí. The Magrittes’ 45-year marriage inspired Paul Simon’s paean to quiet marital bliss, Rene & Georgette Magritte With Their Dog After The War.

But behind Magritte’s staid appearance was a subversive personality. Every one of his paintings was created for political ends.

He was active in the communist party, although he disagreed with its labelling of high art and literature as bourgeois: “class consciousness is a basic necessity, but this does not mean that the workers need to be condemned to bread and water and that it is wrong to wish for chicken and champaign. They are communists precisely because they aspire to a higher life, worthy of man.” Also contrasting him with the other surrealists, Magritte was well versed in philosophy—he was a student of Freud, Marx, and Heidegger, and even exchanged letters with Foucault.

Magritte was also an under-appreciated writer, and an artist who saw painting as just one method for conveying his ideas.

The Treachery of Images

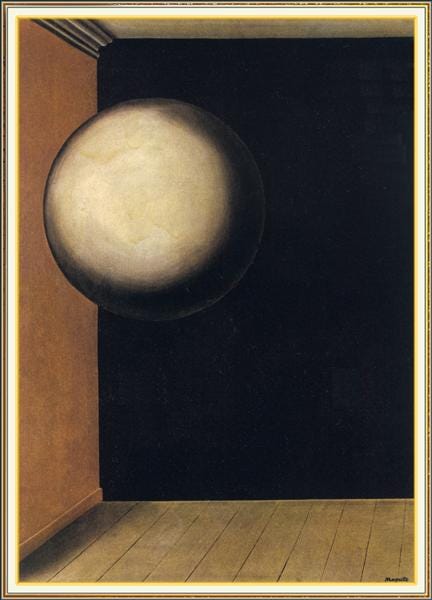

At his core, Magritte was preoccupied by the relations between signs and what they signify: When do signs modify what they are signifying? When do the signs take on a life of their own, and displace the reality they are supposed to represent? What happens when different methods of signification (i.e. words vs. pictures) intertwine? How has our constant reliance on language and images made us forget the true nature of objects?

As previously covered on Hidden Threads, Western painting changed a great deal from the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th. Rather than seeking to create realistic depictions of a three-dimensional world, painting sought to give color, vitality, and substance to unconscious desires, inner feelings, and symbolic connections. But even the paintings of the most avant-garde modernists did not question the existence of the reality the realists tried to depict, in the way that Magritte’s paintings seem to do.

Taking a page from Foucault, we see that with Magritte two unstated assumptions of Western painting no longer hold: that an object in a painting is a representation of its real-world counterpart (likeness = representation), and that different modes of representation (i.e. words and pictures) cannot mix.

Two principles, I believe, ruled Western painting from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. The first asserts the separation between plastic representation (which implies resemblance) and linguistic reference (which excludes it) . By resemblance we demonstrate and speak across difference: The two systems can neither merge nor intersect.

The second principle that long ruled painting posits an equivalence between the fact of resemblance and the affirmation of a representative bond. Let a figure resemble an object (or some other figure), and that alone is enough for there to slip into the pure play of the painting a statement-obvious, banal, repeated a thousand times yet almost always silent…"What you see is that .”

Instead of a painting that seeks to resemble the world based on its realistic-ness, or its emotional content, we got a painting which says, scrawled like a teacher’s script on a blackboard, “this is not a pipe”. An explicitly non-representational painting. Magritte’s paintings aren’t an abstract rendering of something real, they are calling out the world we live in as fake. They aren’t abstract at all, they are literal to an unsettling degree.

But what is left of a painting if it doesn’t look like anything? It becomes a picture of our minds, a picture of how we create and perceive images. It also becomes a picture of how we look for meaning in images. Magritte’s paintings are often so stirring that we assume that there must be some intended, hidden meaning behind them. They work to draw attention to what is hidden, what lays behind the painting without giving us any glimpse of it. But is there really anything hidden? Or are these just surrealistic one-liners? As Magritte says himself:

My paintings resemble paintings. My paintings is a mind seeing without naming what it sees. What it sees on an object is another hidden object.

Likeness is identified with the essential activity of the mind: that of likening something to something else…the art of painting…cannot articulate ideas, nor express feelings: the image of a face weeping does not express grief, not does it articulate an idea of grief, because ideas and feelings have no visible form.

Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.

Magritte the Marxist

Magritte modeled his paintings on the pseudo-reality of the growing advertising industry. In the newly mass production-based post-war economy, city-dwellers were for the first time being subjected to a constant stream of images telling them how to live, what they want, and who they should be. Magritte believed that our fetishistic relation to commodities had separated us off from both a more grounded, and a more spiritual, reality.

The bourgeois order is an order of disorder. Extreme confusion deprived of all contact with the world of necessity.

Perhaps the most creative theorist of the new image and advertising-based society was Jean Baudrillard. Baudrillard believed that this society, to an extent not seen before, was based on the sign value of an object, not its use value. (Take Nike as an example of sign value—the high price tag of the shoes is not the result of high production costs, or particularly high quality materials or craftsmanship. The consumer is paying a steep cost to buy the idea which Nike symbolizes. The consumer is buying a symbol of athleticism, drive, and a “just do it” mindset. The transaction is no longer primarily a question of the physical properties of the shoe).

As technology provides new means for entertainment, information dispersal, and communication, the proliferation of signs has metastasized into a hall of mirrors, an encompassing simulation. The ‘real’ which these signs used to signify, or used to mask, has largely been lost. The speed and intensity of the spread of information, Baudrillard believed, had created a “hyperreality” which provides the consumer with experiences more intense and involving than banal everyday life.

It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real…It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory.

Disneyland is a perfect model of all the entangled orders of simulacra. It is first of all a play of illusions and phantasms: the Pirates, the Frontier, the Future World, etc. This imaginary world is supposed to ensure the success of the operation. But what attracts the crowds the most is without a doubt the social microcosm, the religious, miniaturized pleasure of real America, of its constraints and joys. By an extraordinary coincidence (but this derives without a doubt from the enchantment inherent to this universe), this frozen, childlike world is found to have been conceived and realized by a man who is himself now cryogenized: Walt Disney, who awaits his resurrection through an increase of 180 degrees centigrade.

Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, whereas all of Los Angeles and the America that surrounds it are no longer real, but belong to the hyperreal order and to the order of simulation…This world wants to be childish in order to make us believe that the adults are elsewhere, in the "real" world, and to conceal the fact that true childishness is everywhere - that it is that of the adults themselves who come here to act the child in order to foster illusions as to their real childishness.

Magritte’s drawings take place in a world where signs no longer represent the things they signify. The objects of his paintings no longer function like their real-world equivalents—they “become weightless, shapeless, negated, depleted, freely exchanged and interchanged.” They take on a new, mysterious intrinsic essence.

This calls attention to Marx’s prediction that the rapidly expanding capitalist order would disrupt all traditions, all the ancestral methods of craft and production, that things would no longer stay in their place and carry with them their long-held meanings. As Marx famously wrote, “all fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.”

The Uncanniness of Magritte

But are Magritte’s paintings, a depiction, an expression, an endorsement of this new hyperreality? Certainly not. If anything, they are re-enlivening the mystery of the mundane. They seem attached to an ancient mystery, not a novel rootlessness. Magritte’s objects are not controlled by the circulation of the economy or mass production, they seem to act on their own accord: “We rarely think of things until we wish to control them. We don’t dwell in the mysteries they hold.”

Magritte’s objects radiate an uncanny sort of energy, or even a feeling of deja vu. In his essay on the uncanny, our old friend Sigmund Freud draws attention to the word’s german equivilent, unheimlich, which means un-homeliness or not-at-home. The uncanny is when the unfamiliar seeps out from the core of the familiar, when we are at home, but it isn’t quite our home.

In the essay, Freud identifies two primary causes of the sensation of the uncanny. The first is when an internal, parasitic, force makes a familiar object or person act in an unfamiliar way.

[this is apparent when there is] doubt whether an apparently animate being is really alive; or conversely, whether a lifeless object might not be in fact animate…The uncanny effect of epilepsy and of madness has the same origin. The ordinary person sees in them the workings of forces hitherto unsuspected in his fellow-man but which at the same time he is dimly aware of in a remote corner of his own being. The Middle Ages quite consistently ascribed all such maladies to daemonic influences, and in this their psychology was not so far out.

The second cause of an uncanny sensation is when forms of childlike thought re-emerge after they’ve been surpassed. Freud believed that every individual must pass through several stages of psychical development as a child in order to form their personality and become a healthy adult. During these stages, the child’s mind is subject to many illogical fears and sensations, and works in a manner which is more symbolic than logical. Contemporary scientists and anthropologists largely agree with Freud on this count. As Tanya Luhrmann explains, “what happens developmentally, is that young children do not separate their mind from the world. They often experience their mind as affecting things in the world. If you tell a two year old to hide, the two year old will sometimes shut his or her eyes because they believe that if they can’t see they can’t be seen.”

During adulthood, certain experiences and fears can then precipitate the re-emergence of these submerged modes of thought.

Let us take the uncanny in connection with the omnipotence of thoughts, instantaneous wish-fulfillments, secret power to do harm and the return of the dead. The condition under which the feeling of uncanniness arises here is unmistakable. We—or our primitive forefathers—once believed in the possibility of these things and were convinced that they really happened. Nowadays we no longer believe in them, we have surmounted such ways of thought; but we do not feel quite sure of our new set of beliefs, and the old ones still exist within us ready to seize upon any confirmation. As soon as something actually happens in our lives which seems to support the old, discarded beliefs, we get a feeling of the uncanny; and it is as though we were making a judgment something like this: “So, after all, it is true that one can kill a person by merely desiring his death!” or, “Then the dead do continue to live and appear before our eyes on the scene of their former activities!”, and so on…

…an uncanny effect is often and easily produced by effacing the distinction between imagination and reality, such as when something that we have hitherto regarded as imaginary appears before us in reality, or when a symbol takes over the full functions and significance of the thing it symbolizes, and so on. It is this element which contributes not a little to the uncanny effect attaching to magical practices. The infantile element in this, which also holds sway in the minds of neurotics, is the over-accentuation of psychical reality in comparison with physical reality—a feature closely allied to the belief in the omnipotence of thoughts.

“The darkest eyes enclose the lightest.” Mystery is not one of the possibilities of reality. Mystery is what is absolutely necessary for reality to exist.

The Strange Afterlife of Magritte

Hal Ashby’s Being There (1979) is essentially Magritte: the movie. In the film, Chance, a simple-minded man in a bowler hat and suit leaves his role as gardener on a large estate, when its wealthy owner dies. Throughout the movie, nearly everyone interprets Chance’s simple and calm nature as wise and enigmatic. He eventually unintentionally wins the confidence of the a dying mirror-making tycoon, the President, and the American public. Because Chance does not understand the situations he is in, he is not intimidated by them. Because Chance is essentially a blank slate, everyone around him projects what they want to see on to him. Everyone fills the blank lack within Chance with what it is they are looking for. In a surreal sequence at the end of the film, Chance finds that he can walk on water.

Perhaps more so than any of the other surrealists, Magritte’s paintings have entered the collective consciousness. His paintings have been used for advertisements, album covers, book sleeves—becoming a brand identity unto themselves. But no painting of Magritte’s is as instantly recognizable as The Son of Man:

This painting, along with the 1966 painting Le Jeu De Morre, (owned by Paul McCartney), inspired the Beatles to name their record company Apple Corps.

Because of his love for the Beatles, a young Steve Jobs decided to name his nascent computer company “Apple” in tribute to the band. Many lawsuits ensued.

Apple Computer pledged to pay Apple Corps $80,000 for the right to keep the Apple name, and both companies decided to keep their name and respective logos if Apple Corps agreed to never enter the world of computers and Apple Computers agreed to never enter the world of music, and if both agreed only to use their versions of Magritte’s apple image.

And thus, the artist who put an apple in front of one man’s face to call out the distractions and failings of bourgeois life, inadvertently put an apple in front of all of our faces.