Living in an Enchanted Universe (Pt. 2)

Cracks in the Closed Universe & the Artistic Origins of Science

Much of the modern scientific worldview can be traced to an unexpected origin: painting.

For the Medievals, the object of painting was to convey theological concepts through visual symbols and allegory, and to awaken in the viewer “pious empathy and affective piety.” Realism was not the intent—the size of figures was determined by their importance in the story, chronologically disparate events could be depicted in the same scene, and historically anachronistic outfits, appearances, and objects were not seen as an issue. As Barfield explains, the Medievals “felt none of the awkwardness we do about representing invisible or spiritual events and circumstances by material means. The same human figures, costumes, artifacts, etc., could be used in the same picture or carving as literal reproductions of the physical world and as representations of a spiritual world.” Medieval paintings were supposed to represent the ‘view from Heaven’—nothing important is hidden behind another object, or cut off by the edges of the picture, and the spiritual story which animates history, and the Godly purpose of our life on Earth, is illuminated.

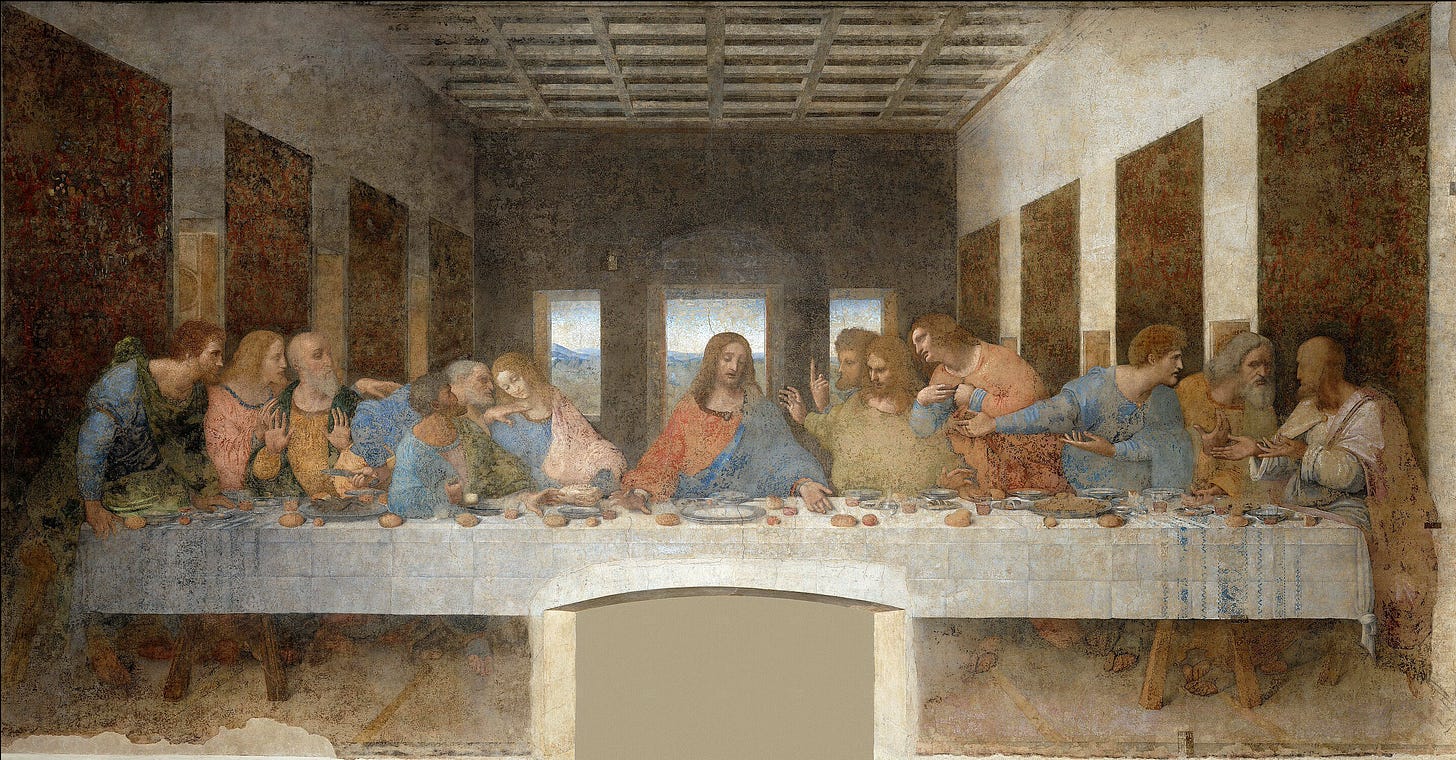

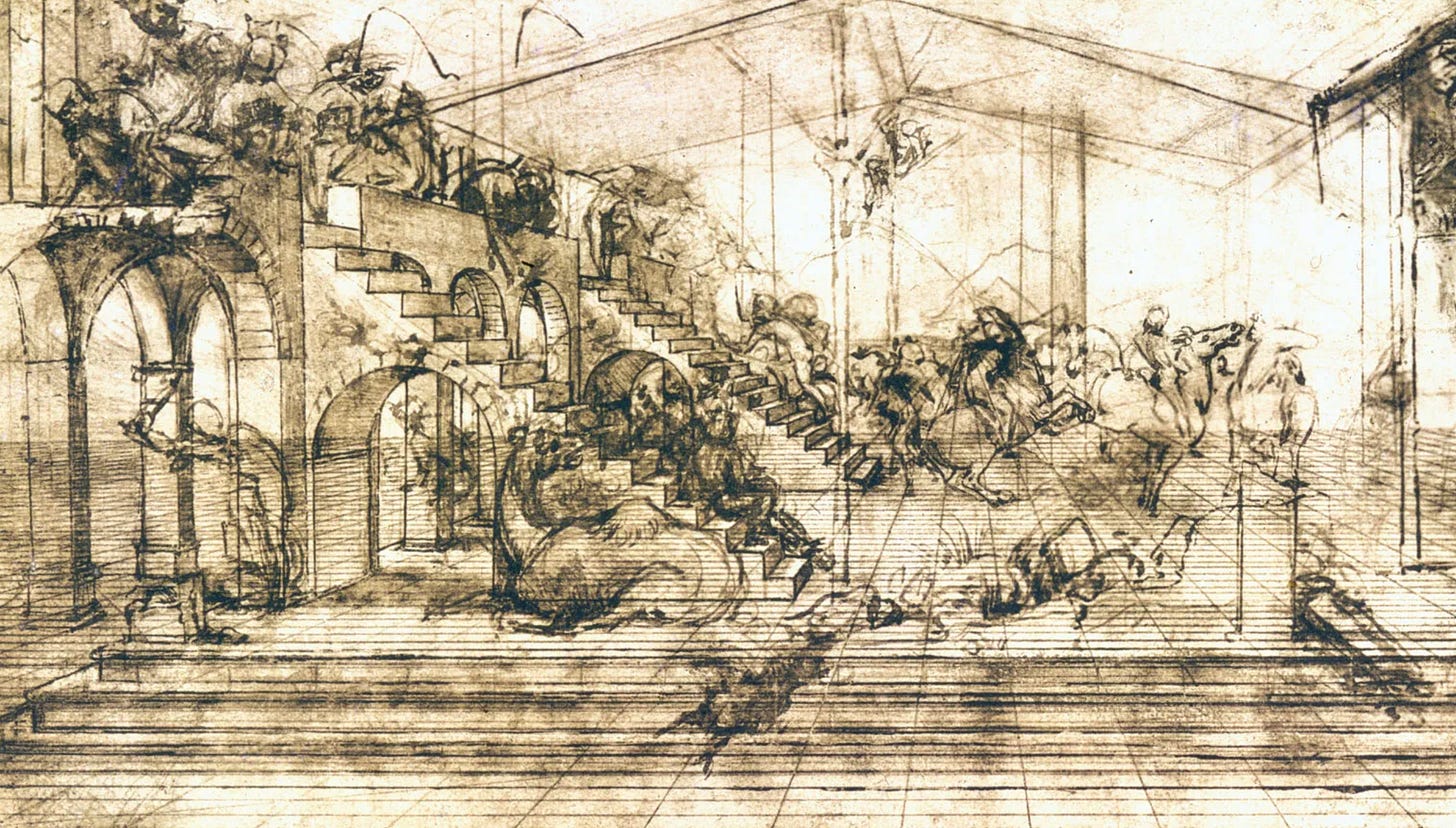

Renaissance painters, culminating in Leonardo Da Vinci, had a different view as to the aspirations of painting. Da Vinci sought to mathematize the world—both through the creation of mechanical structures, and through drawing figures in proportionally accurate ways. He did not see his artistic and engineering feats as in any way separate; both were about grasping the world with ever-increasing precision. Whereas the Medievals used painting to bring the viewer from the world of the physical into the world of the super-physical, Da Vinci made Renaissance painting about bringing the viewer from the super-physical into the physical.

Even as a scientist, Leonardo insists upon this visibility, this graspability of the form. He considers it the limit that bounds all human knowledge and conception. To traverse the realm of visible forms completely; to grasp each of these forms in its clear and certain contours; and to keep them in their full definiteness before both the internal and the external eye: these are the highest aims recognized by Leonardo’s science. Thus, the limit of vision is also, of necessity, the limit of conception. Both as artist and as scientist, he is always concerned with the ‘world of the eye’; and this world must present itself to him not in bits and pieces but completely and systematically. — Ernst Cassirer

This quest led Da Vinci to perfect the recently-developed art of perspective painting, the invention of which has been discussed on previous Hidden Threads. For the first time, a bodily sense (sight) was able to be rendered objectively; the way in which humans see the world was able to be ordered and represented mathematically. Sight was also beginning to be seen as something which can be developed to be more rational, to be trained to capture a more accurate view of the world. Paintings began to be experienced the way someone would look through a window into another room, instead of peering into a looking-glass to see an allegorical/mythical representation. The subduing of sight to rational order changed humanity’s view of light and space. As Gebser writes in The Ever-Present Origin, Da Vinci’s writings contain the first “detailed discussion of light as the visible reality of our eyes and not, as was previously believed, as a symbol of the divine spirit.”

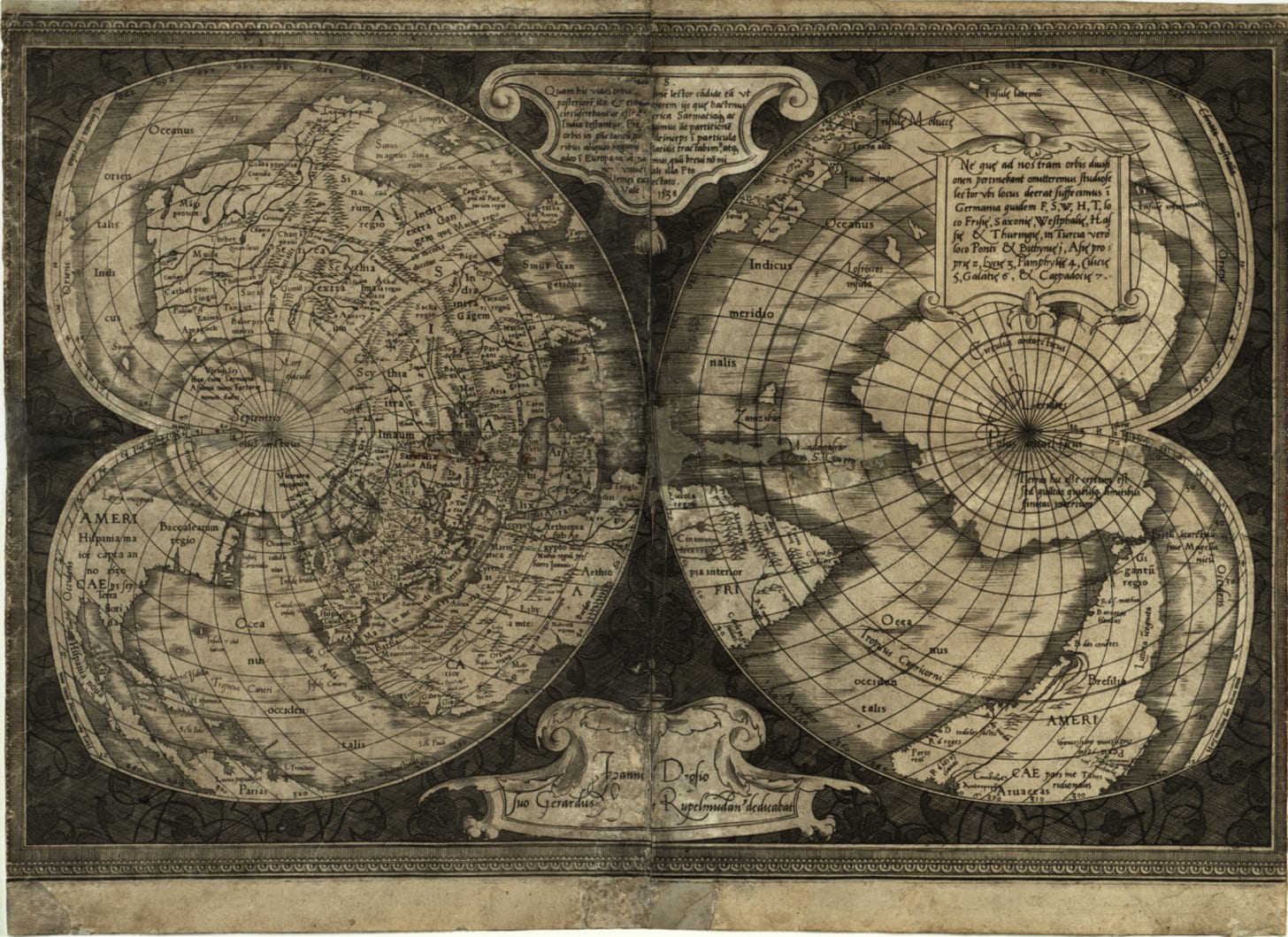

These insights did not remain confined to painting for long. It is almost like the realm of rational spatiality simultaneously opened up in many different domains. Just twenty years after The Last Supper was finished, Diogo Ribeiro oversaw the creation of the first ‘scientific world maps’ based on empiric latitude observations. In the mid-1500’s Gerardus Mercator was the first to use geometric techniques to project the three dimensional surface of the globe onto a two-dimensional surface. The invention of the Mercator Projection changed navigation forever by using “mathematically determined coordinates and straight axes of longitude and latitude to accurately represent relative physical distances on the spherical plane of the globe.”

Meanwhile, the taboo against human cadaver dissection began to wane, and the interior space of the body was mapped. Vesalius and Harvey used their research on the newly-understood circulatory and muscular systems to deliver some of the first major blows against Galen and Hippocrates. And, finally, as we’ll discuss in more detail later on, the conception of a sphere of fixed stars surrounding the Earth began to be replaced by the conception of an infinite, or near-infinite, spatial universe.

The Telescope and The Production of Facts

Da Vinci’s studies in perspective proved extremely formative for a young mathematician from Florence, named Galileo Galilee. Initially, Galileo had wanted to be a painter, but was discouraged by his father. Still, Galileo managed to study at the Florentine Design Academy, where he learned technical drawing and studied perspective. Galileo remained interested in the powers of sight, and the ways in which artists like Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian were able to rigorously grasp reality. Soon, Galileo would do to outer space what Da Vinci had done to painting.

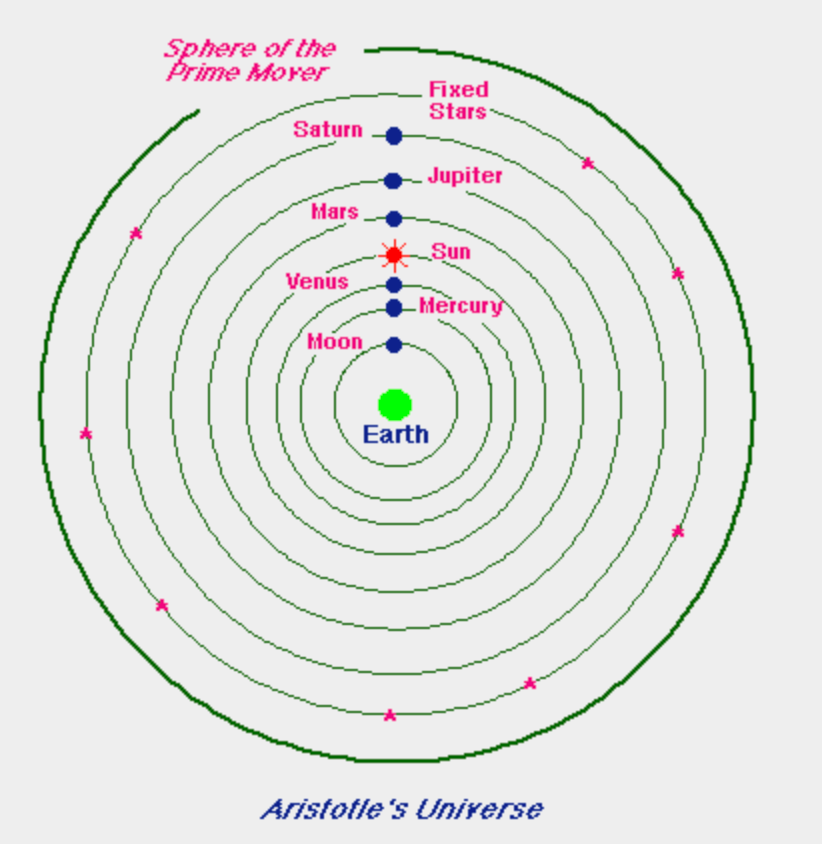

In 1609, Galileo heard about a strange newly invented device from Holland that was rumored to make distant objects appear as if they were much closer. Galileo quickly got his hands on one of these devices and began improving upon it. Soon, he had a telescope that could magnify objects to 30x their size. When he trained this device on the heavens, what he saw was completely unexpected and seismic: the Moon had an irregular surface battered with mountains and craters; there were thousands of stars beyond the sphere of ‘fixed stars’ which were too faint to see with the unaided eye; Jupiter had moons (it was believed that only the Earth had a moon); Saturn had rings. And, crushingly, Galileo’s observations soon showed with sense-certainty that the Earth was not the center of the universe.

Galileo’s discoveries didn’t just expand knowledge; they fundamentally changed our understanding of what knowledge is. Before the telescope, nature was thought to reveal her secrets to man through contemplation and revelation. God had made the world intrinsically knowable, and if one couldn’t figure out a problem, one could consult the greatest contemplator on the subject—which was typically Aristotle. (Aristotle was so revered in the Medieval era that if someone was publicly accused of rejecting one of the philosopher’s tenets, they could be charged with holding a position contrary to the word of God and be punished by the state). But now, a tool had triumphed over the mind of man. Simply looking through this device proved that the best the unaided human mind could come up with, and believed in for thousands of years, was completely wrong.

Prior to Galileo, the thinkers of the Renaissance thought that they were merely re-discovering knowledge which was already known to the much-hallowed Ancients. Great minds like Bruno, Kepler, Copernicus, Pico, Alberti, Ficino, believed (and were often correct) that they were re-obtaining knowledge that was lost during the Dark Ages. They consulted the Jewish Kabbalah, the Corpus Hermeticum, and Plato, as much as they did the natural world around them, in search of answers. This is difficult for us moderns to wrap our heads around, but until the 1600’s, it was essentially the case that the older the source of knowledge, the more respected and authoritative it was deemed to be. After Galileo, however, an understanding arose that what was happening in Renaissance Italy was something the world had never seen before. The telescope and subsequent inventions gave the Renaissance thinkers the tools necessary to forever break with the past.

“In this little treatise I am presenting to all students of nature great things to observe and to consider. Great as much because of their intrinsic excellence as of their absolute novelty, and also on account of the instrument by the aid of· which they have made themselves accessible to our senses.” —Galileo

But what the telescope produced was not greater certainty in the rigor of our knowledge, but a pervading sense of doubt—doubt that our minds and our senses could accurately perceive the world. If our senses could be so fundamentally deceived about something as basic and emblematic as whether the sun goes around the Earth, how could they again be trusted? As Hannah Arendt formulated, “The modern astrophysical world view, which began with Galileo, and its challenge to the adequacy of the senses to reveal reality, have left us a universe of whose qualities we know no more than the way they affect our measuring instruments.”

Galileo’s discoveries also sped up the process by which the folded-universe, the universe of the microcosm and the macrocosm, the universe in which the sky reflects and influences the Earth, lost its coherency. It was once thought that all planets moved in circles, because circularity symbolized Godly perfection. It was also thought that everything in the sky above influenced the story playing out on Earth—but how could stars so far that we couldn’t see them have anything profound to do with Earthly lives? What did a seemingly infinite universe tell us about God’s relation to man?

The conception of the world as a finite and well-ordered whole, in which the spatial structure embodied a hierarchy of perfection and value, [gave way to] that of an indefinite or even infinite universe no longer united by natural subordination, but unified only by the identity of its ultimate and basic components and laws.—Alexandre Koyre

As Arendt wrote, “the more man learned about the universe, the less he could understand the intentions and purposes for which he should have been created.” As the world got bigger—as we discovered far away stars, and far-off continents, the world also got smaller. It got smaller because we were able to reduce the world to systems of coordinates, reduce it down to numbers and patterns. Where before the world was enchanted by living agents and essences, it instead began to be filled with consistent physical laws and mechanical properties.

Inventing the Controlled Experiment

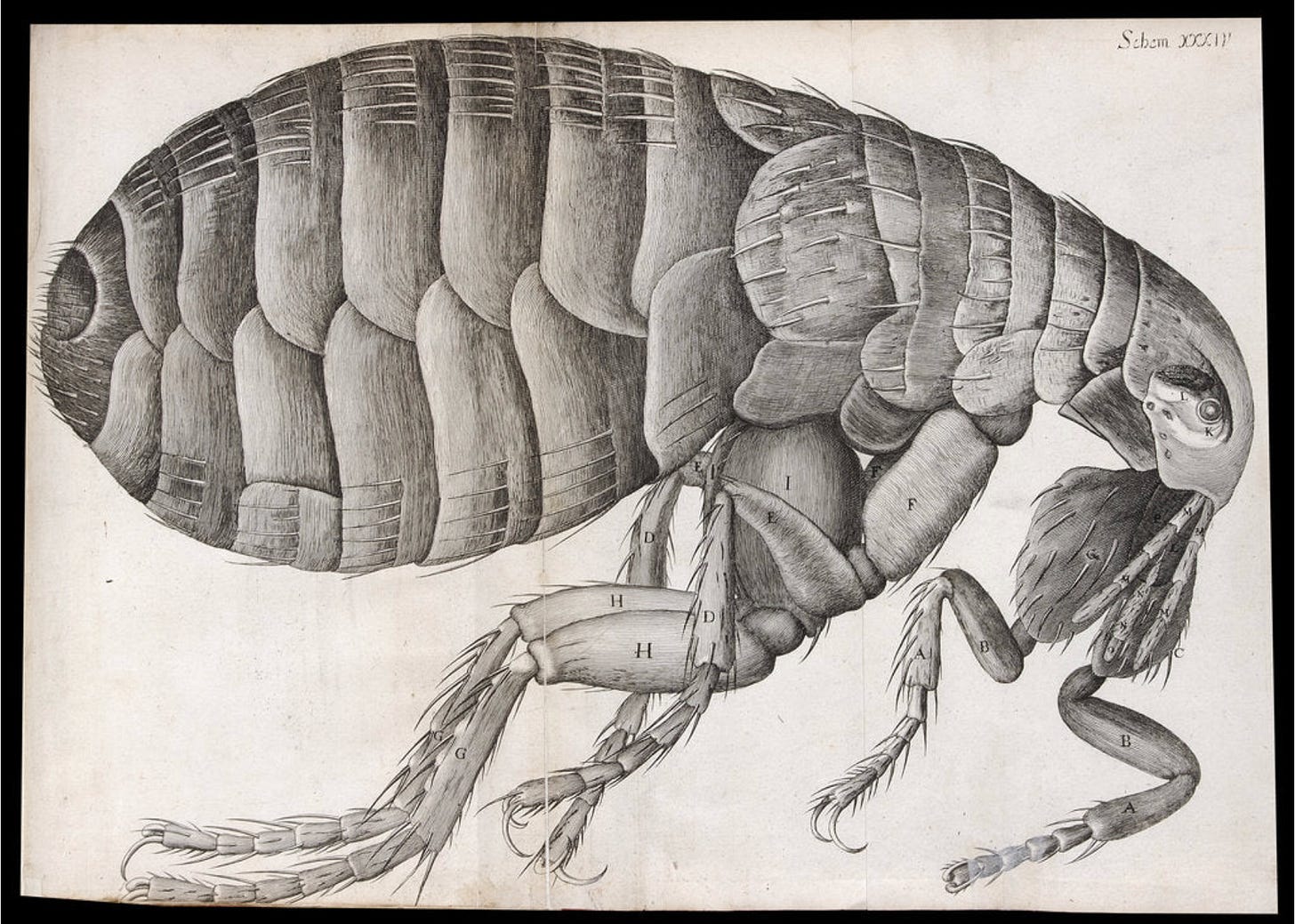

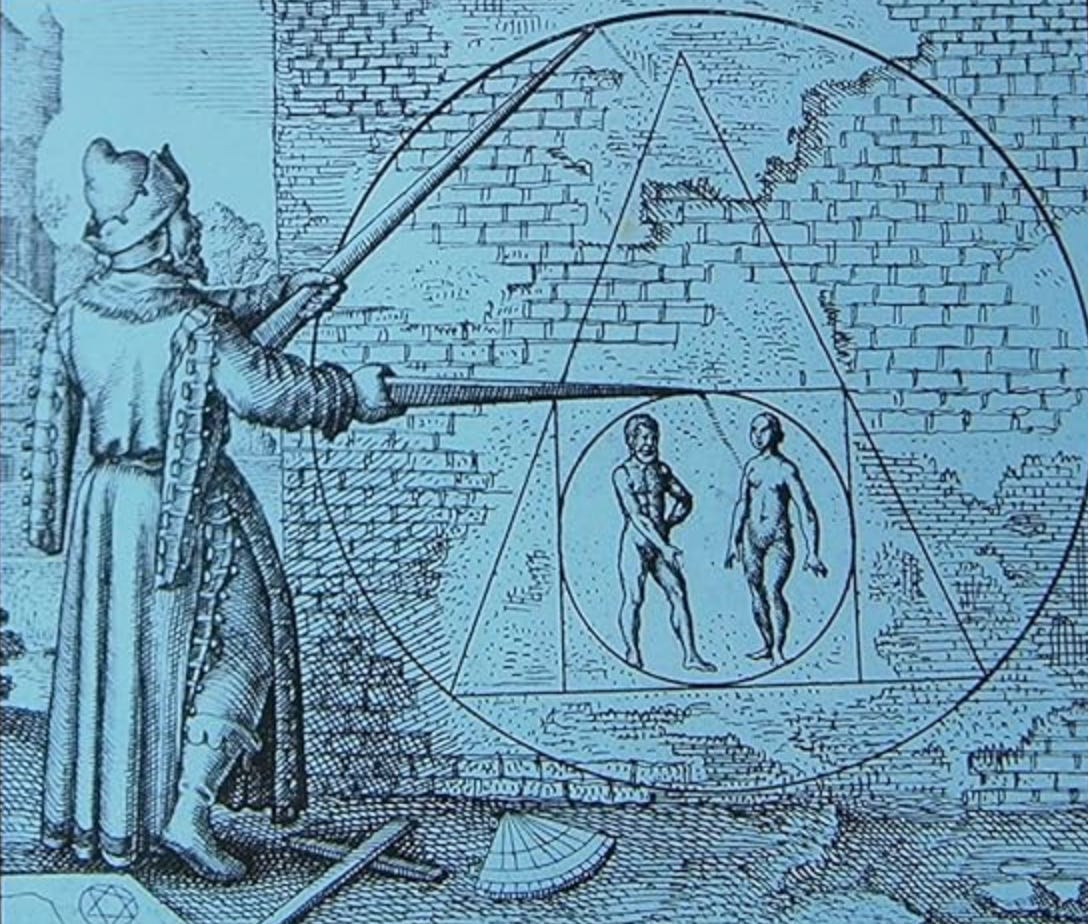

Following the development of the telescope, there began an obsession with using tools to find the reality which lay behind deceptive appearances.

Inverting Galileo’s tool, Robert Hooke began training his microscope on another world hitherto unseen. All sorts of features of the physical world that were completely unpredictable were revealed, such as the existence of plant and animal cells, the hidden barbs on a rosemary leaf, the complex compound body and tiny hairs of a flea. Hooke began to understand that by looking at the microscopic structure of objects, rather than studying their symbolic resemblances and analogical place within the universe, he could understand their physical properties.

For Hooke, the future of humanity’s intellectual development lay in creating instruments to remedy the "infirmities" of the human senses." With “artificial organs” it was possible to enlarge the “dominion of the senses.” He further speculated that in the future, “tis not improbable, but that there may be found many Mechanical Inventions to improve our other Senses, of hearing, smelling, tasting, touching." While this prediction sounds whimsical, he was right: smoke detectors pick up particles of smoke just like the human nose does; machines can pick up the audio frequencies of music, the high-pitched pulses of animals, and earthquakes. Science is now, in large part, the use of machines to perceive and take measurements of phenomena too subtle for the unaided senses.

Another massive step towards the ‘instrumentalisation’ of knowledge was also taken by Hooke, along with his teacher, Robert Boyle. The pair developed the air pump, which could be used to create a vacuum or increase the air pressure inside a glass cylinder. The experiments they conducted with the air pump were a prototype of how science could be done—creating a closed system in which the dependent variable could be changed, and the independent variable measured. Using the air pump, they were able to formulate Boyle’s law (P1V1 = P2V2, which is familiar to most high school chemistry students), showed that fire depends on air, and managed to suffocate a large number of small animals.

Prior to Boyle and Hooke’s work, experimentation was not seen as a helpful mode of knowledge creation. The Medieval-Aristotelian worldview held that “Once you take something out of its natural environment, it is not behaving in its natural way. To grasp its nature, you must observe it in its natural environment. Observation and contemplation makes sense of the world.” Creating a controlled experimental space like the air pump was seen as unnatural, a deformation of nature, and therefore not a good way to understand the mind of God, or how he had ordered his universe. Many critics were dumfounded by Boyle and Hooke’s experimental approach, which appeared focused on creating "matters of fact," rather than allowing nature to reveal herself to man. As Hannah Arendt again explains:

Where formerly truth had resided in the kind of "theory" that since the Greeks had meant the contemplative glance of the beholder who was concerned with, and received, the reality opening up before him, the question of success took over and the test of theory became a "practical" one—whether or not it will work. Theory became hypothesis, and the success of the hypothesis became truth.

Descartes’ Mental Coordinates

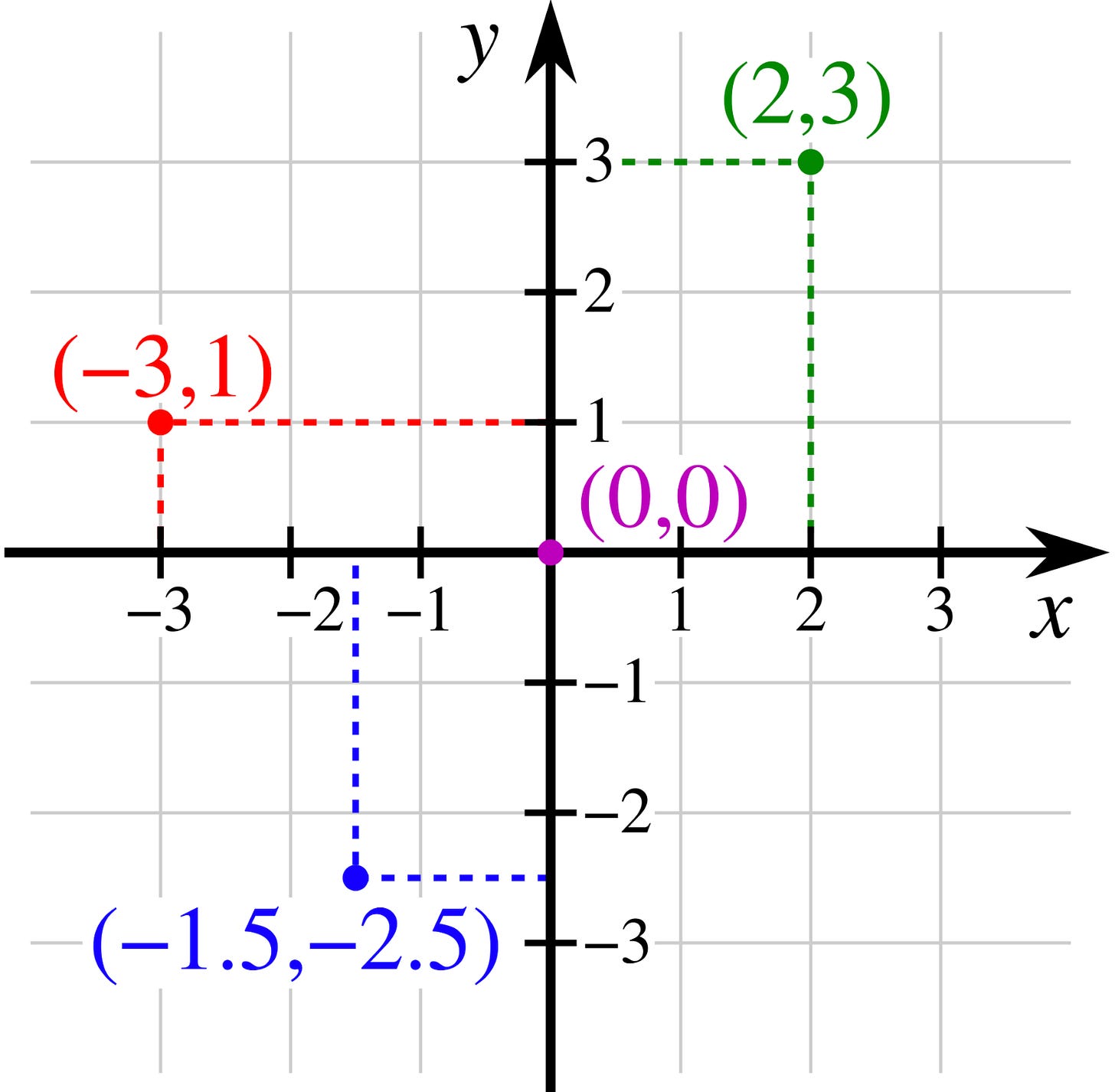

The story goes that Descartes was lying in bed, watching a fly crawl across his tiled ceiling. In a stroke of genius, Descartes realized that he could identify the position of the fly using only two numbers, by describing where the fly was on an ‘x axis’ and a ‘y axis.’ Descartes then realized that he could describe the fly’s location in three dimensions, by assigning a vertical, or ‘z axis.’ This story is almost certainly not true, but it does accurately convey that Descartes developed the concepts necessary to create the Cartesian Coordinate system, familiar to all from elementary mathematics.

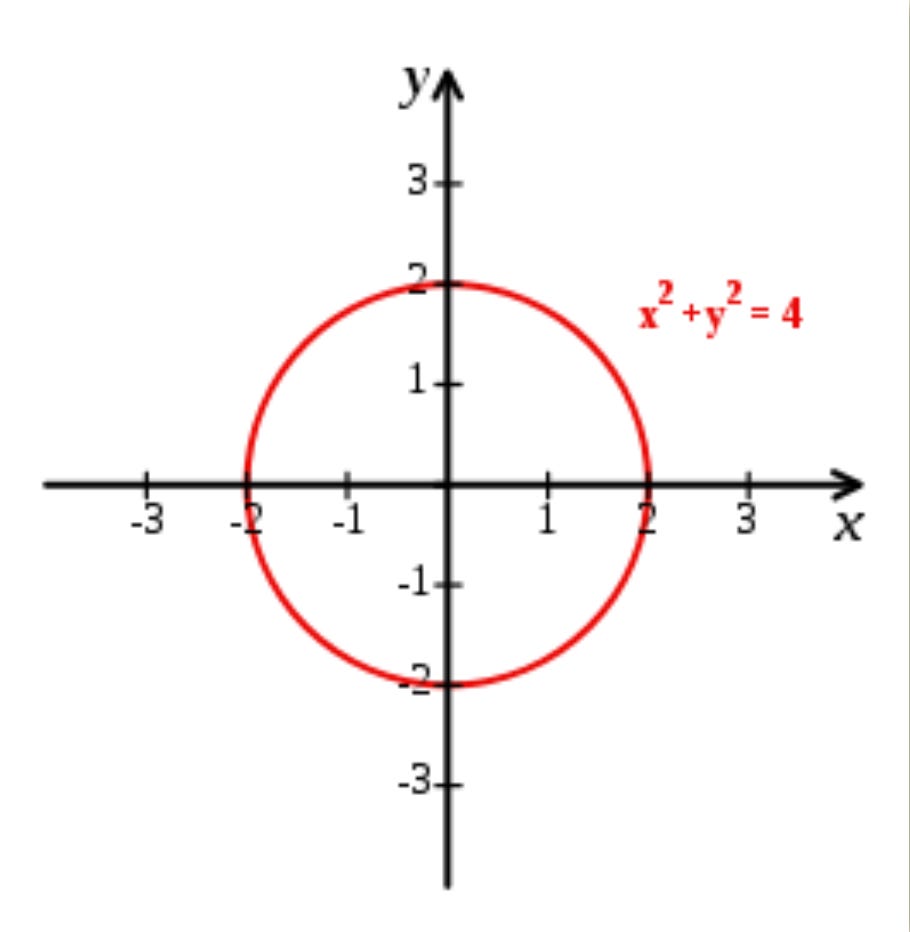

Descartes’ discovery, which revolutionized mathematics, was that problems of geometry could be expressed, and solved, using algebra. Thus, whereas Da Vinci reduced three-dimensional space to geometry, Descartes reduced geometry to algebraic formulae. Descartes also realized that any phenomenon which took place spatially could be graphed geometrically. The world could now truly be rendered mathematically; the planets revolving through space, the force of gravity bringing a thrown rock to Earth; topographical maps; could all now be represented by a simple graph or a line of algebraic symbols.

For one of the most important thinkers in world history, there is surprisingly little written about the connections between Descartes’ mathematical and philosophical breakthroughs. Descartes famously, inspired by the great wave of doubt following Galileo’s discoveries, decided to doubt all sense experience. Using his method of extreme doubt, Descartes was only able to believe with certainty in his own existence, mathematics, God, and the content of his own thoughts. Descartes also believed that using mathematics (In a few moves too complex to fully explain here), a consistent model of the external world could be created. Descartes’ coordinate system, and the mathematical ideas which led to it, allows him to reduce the physical world to a system of thought which is both consistent and graspable.

When Descartes' analytical geometry treated space and extension, the res extensa of nature and the world, so "that its relations, however complicated, must always be expressible in algebraic formulae," mathematics succeeded in reducing and translating all that man is not into patterns which are identical with human, mental structures. When, moreover, the same analytical geometry proved "conversely that numerical truths . . . can be fully represented spatially," a physical science had been evolved which required no principles for its completion beyond those of pure mathematics, and in this science man could move, risk himself into space and be certain that he would not encounter anything but himself, nothing that could not be reduced to patterns present in him.

Even then it was clear that modern mathematics, in an already breathtaking development, had discovered the amazing human faculty to grasp in symbols those dimensions and concepts which at most had been thought of as negations and hence limitations of the mind, because their immensity seemed to transcend the minds of mere mortals, whose existence lasts an insignificant time and remains bound to a not too important corner of the universe. —Hannah Arendt

By ordering the world mathematically, by siphoning its movements down to equations, by reducing its events to data, its causes to mechanisms, humankind could shrink the world down in the same way a map shrinks down a territory. It could make a mental model that could order the external world with a degree of certainty. It was no longer necessary to understand the world through its emotional and symbolic content, its implied purpose and various connections to scripture and revelation—all of which were now subject to doubt.

We can now review how Descartes’ system of ordering the world, graphically and algebraically, displaced the Medieval-Renaissance form of knowledge production. In the Medieval-Renaissance period, connections between things were already intrinsic to God’s ordering of the world. People discovered the connections which God had laid down through resemblance, analogy, and sympathies. We looked for teleologies and attractions, like the world was a living creature.

In Descartes’ world, we lay systems of ordering upon the world like a grid. Humanity does not discover a taxonomy laid down by God, but uses reason and mathematics to create a functional, workable, order to catalogue the world. Rather than looking for resemblances, we build sequences based on identity, difference, and measurement. We can draw distinctions between things based on non-mathematical properties, but we know that these distinctions are subjective, and therefore subject to doubt. As Foucault explains:

The activity of the mind…will therefore no longer consist in drawing things together, in setting out on a quest for everything that might reveal some sort of kinship, attraction, or secretly shared nature within them, but, on the contrary, in discriminating, that is, in establishing their identities, then the inevitability of the connections with all the successive degrees of a series.

Finally, God does not exist in Descartes’ external world. God is what makes this world knowable, thinkable to us. God does animate our minds the way the soul animates the body. But God does not appear as that which pushes the planets on their orbit—the movement of the planets is only motion applied to geometry. God is also not what made the walnut look like the human brain, and God is not that which is heard in a rushing stream.

As Alexandre Koyre writes, “Descartes' God, in contradistinction to most previous Gods, is not symbolized by the things He created; He does not express Himself in them. There is no analogy between God and the world; no imagines and vestigia Dei in mundo; the only exception is our soul.” Descartes does not imbue external nature with God, in the manner of the Achuar, the Crow, or the Medieval Europeans. Nature for Descartes is something objective and universal; culture is the only realm in which God may play an active role. We’ve gone from a world in which almost every part of an individual’s identity (their society, their family, their afterlife), was in reference to God, to a world where God, at most, is an abstract presence.

These three ingredients—the experimental method, the use of instruments which can go beyond sense perception, and the ordering of the natural world through either mathematical or self-consciously human-made subjective categories—create the scientific worldview. They are why most of us don’t believe that caribou offer themselves up for the hunter.

Part III: The Myth of Disenchantment?

Perhaps the fact about our contemporary world that would have most shocked the great thinkers of the 19th and 20th centuries—Marx, Freud, Mill, Arendt, Russell, Popper, Einstein, Beauvoir, etc—would be the persistent importance, and even comeback, of religion. The story we’ve told above is one of reason overcoming dogma, and scientific thought overtaking myth and magic. But is this really the whole story? Soon, the most powerful country on Earth will have an election in which religion is a decisive factor. Humans the world over still consult spirits, gods, and supernatural omens.

The number of Americans who believe in supernatural phenomena has declined rapidly in the last fifteen years. However, the numbers are still quite high. 74% of Americans believe in God, 69% believe in angels, 59% in hell, and 58% in the devil. In 2019, a poll found that 46% of Americans believe in ghosts, 45% believe in witches, and 33% believe in reincarnation. In 2015, a YouGov survey found that 48% of Americans agreed with the claim “Some people can possess one or more types of psychic ability (e.g., precognition, telepathy, etc.)” Ask your friends and family, and you’ll be surprised how many around you have had encounters with the (potentially) paranormal.

The Magicians Who Made Modernity

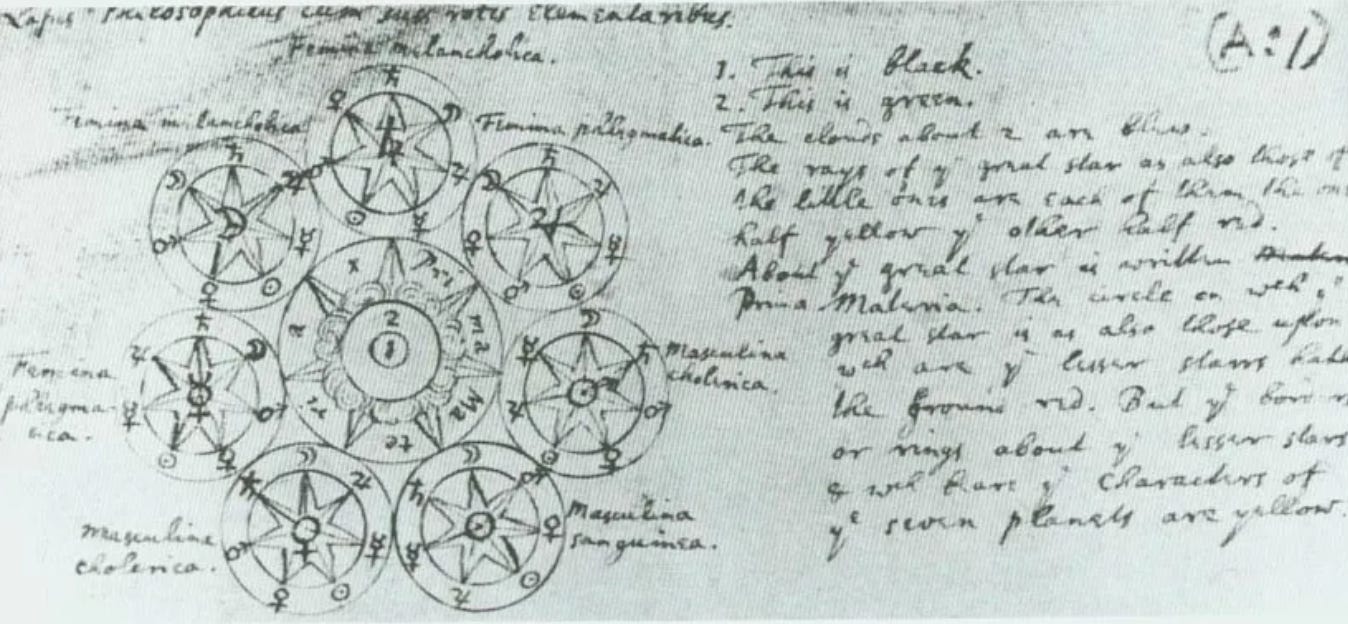

As argued in Jason Ānanda Josephson Storm’s book, The Myth of Disenchantment, many of those who ushered in the scientific revolution did not think of themselves primarily as scientists at all. Towering figures like Newton, Descartes, Bruno, Kepler, Boyle, and Bacon, all largely saw themselves as mystics or as magicians.

Newton is a particularly strong case. He spent much more time writing about alchemy and secret codes hidden in the Bible than he did on gravity. He also left behind more than 650,000 words on Hermeticism. As John Maynard Keynes, who bought much of Newton’s handwritten notes, famously put it: “Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians.”

Descartes is a fascinating example as well. Contrary to popular perception, he did not develop the basis of his ‘new science’ through logical deduction. It came to him through mystical dreams. In early November 1619, Descartes wrote that he felt that he was being possessed by a great enthusiasm, or even a spirit. He wrote that something beyond human intelligence was warning him about an upcoming epiphany.

On the night of November 10, 1619, Descartes had a series of three dreams which unlocked his philosophy for him. In the first dream, Descartes is surrounded by a swarm of ghosts while walking down the street. The ghosts swirl around into a giant gust of wind, which ushers him into a Church. He is then given a melon from a foreign land. In the second dream, Descartes’ room fills with sparks. In the third dream, two books—a dictionary and a book of poetry by Ausonius—appear before him. Then, the spirit of truth appears in the corner of the room. Descartes begins analyzing the dream while still inside it, and reads from the poetry book, which asks him to rethink the path of knowledge. It is possible that this is the most important series of dreams in human history.

Descartes immediately began consulting esoteric and occult works to try to decipher the meaning of this dreams. He began reading Kabbalah and Rosicrucian works, and may have gone on a spiritual pilgrimage to Notre Dame de Lorette for answers (the historical record is unclear on whether he actually went, but he wrote that he intended to go). Descartes also continued to analyze these dreams throughout his philosophical works. In Meditations I, Descartes wonders if the people he sees in the street are really ghosts, or some kind of automaton. Later he wonders how he can tell whether he is, or isn’t, still inside a dream. When his new philosophical system began to cohere, Descartes thought he was both deciphering something which initially came to him in his sleep, and was rediscovering secret knowledge known to ancient sects.

Why did these pioneers of the Enlightenment have such close ties to the occult? Was it necessary for them to work through the esoteric, in order to transcend it? Were these odd interests the necessary cost of having brilliant, but strange minds? Or, do the development of the sciences and the occult have a more intrinsically intertwined relationship than we like to believe? Do they somehow complement each other?

Modern Ghosts

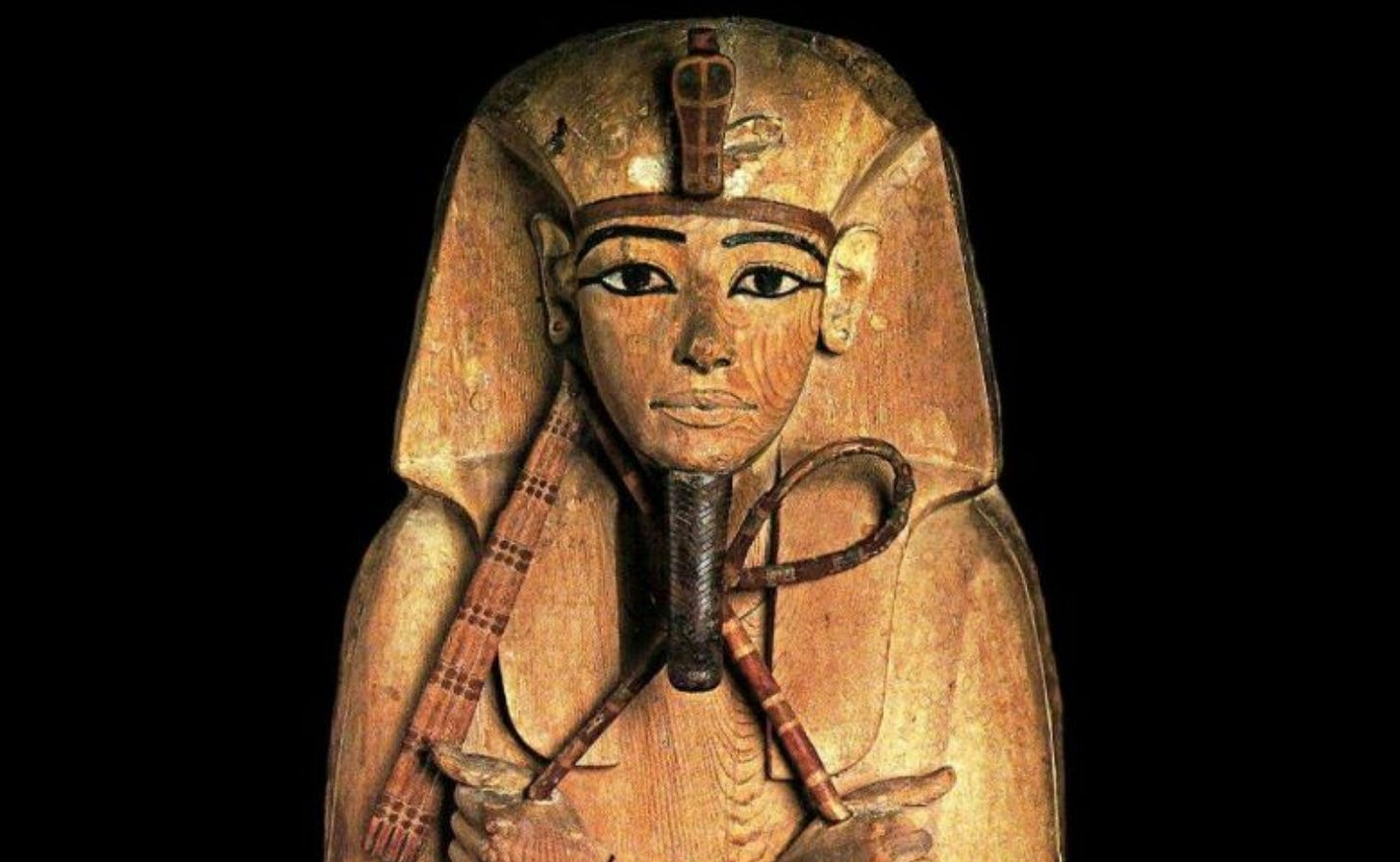

In a very unpopular article, French theorist Bruno Latour wrote that King Ramses II did not die of tuberculosis, but of ‘Saodowaoth.’ In 1976, the mummy of King Ramses II was brought to Paris, and examined by a team of scientists, who determined that the old king had died of an infection caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. Latour argued that this finding was as anachronistic as finding a machine gun, or a Marxist guerrilla movement, in Egypt circa 1213 B.C.. Latour argued that scientists should stick to the original, ancient cause of Ramses’ death, which was called Saodowaoth. Latour’s point was that facts cannot be separated from the networks of their production.

All of our facts are created through a network of social (subjective) and natural (objective) relations. As we get further away from the hard science (physics, mathematics), our definition of objects and phenomena become more subjective. We socialize nature, impute subjective categories onto it, in order to have it make sense in our larger framework.

As an example, the borders we draw between different mental illnesses and the lines we draw between ‘healthy’ minds and ‘unhealthy’ minds, have subjective and objective elements. These lines often change over time, reflecting society’s interests, knowledge, and the state of public opinion. Often, it is the popularity or publish-ability of studies, and the direction which grant funding wants to take science, that determines how we conceptualize these subjective/objective hybrids.

Many of the most famous scientific studies, which have had large impacts on society—the marshmallow test, the Stanford prison experiment, power poses, implicit bias tests, the Dunning-Kruger effect—all have either been debunked, or proven to have vastly different implications than the public took them to have. The social sciences, in particular, are in “a replication crisis,” where old studies, when retested, reach the same results less than half the time. While many of these inconsistencies may have resulted from mistakes, it is likely that the replication crisis is in part due to researchers making subjective interpretations of data and drawing subjective conclusions that now belong to a different time.

Latour’s point in the Ramses example is therefore that it took a complex social network of scientists, patients, and machines to derive the category ‘tuberculosis’ and another complex social context to create the category of ‘Saodowaoth.’ Tuberculosis makes as much sense in the context of Ancient Egypt, as their illnesses would make sense in ours.

While I am skeptical of Latour’s argument, it is important to recognize that much of how we make sense of the world still comes from how we project our own meanings onto nature. Strange amorphous presences which only truly exist as ideas (the economy, the value of the dollar, the personhood of corporations) organize our society in much the same way as spirits and ghosts help organize Achuar, Mbuti, and Crow society. It doesn’t matter if a spirit only exists within a tree stump, or a corporation only exists within a P.O. box in Delaware—these subjective/objective hybrids have real consequences. Some may even argue that they have agency.

One cannot doubt the staggering achievements of modern science—from germ theory, to antibiotics, electricity, agricultural techniques capable of feeding billions, the uncovering of DNA, the big bang, and evolution. And one cannot fall into a postmodernist, post-truth, relativistic framework, where every claim to truth, morality, or history, is as good as any other. We do seem to have achieved a more versatile, more fine-grained, and more internally coherent understanding of nature. But we must understand that our lives still are, and have always been, mediated by how we socialize nature, how we invent invisible creatures and spirits to help us organize society, and how we use them to make sense of ourselves.