Heidegger, Babies, and the Split-Brain

The most ambitious, and confusing, Hidden Threads article thus far

I would like the reader to be forewarned that this will be a rather technical and challenging article. It will consider innovative experiments in child psychology, the structure and organization of the brain, and one of the most complex and exasperating philosophers (or, perhaps more accurately, anti-philosophers) in the Western tradition. However, the question we will be pondering is quite basic and accessible to anyone—what does it feel like to be a human? What is most basic and fundamental to our experience of being alive?

By trying to pin down the fundamental nature of Being in technical terms we will clearly be attempting to do the impossible—catching a catfish with a gourd. Hegel famously referred to our sense of Being as the “indeterminate immediate.” In this essay, we will be pondering three constitutive and universal aspects of our sense of Being which will make it both more immediate and less indeterminate. These three constitutive aspects are: (1) it is dualistic, in that the brain uses two competing processes to make sense of the world; (2) It is fundamentally entangled and involved with the physical objects which illuminate its nature; (3) it utilizes and is constituted by a system of core knowledge which exists with us from birth. If this sounds abstract, don’t worry! Keep an open and curious mind and together we will uncover the most primordial aspects of our existence.

The Brain Mediates Conscious Experience

The brain clearly plays a central role in mediating our conscious experience. This is true whether the brain generates our conscious experiences on its own, or is a machine which picks up the signal of our consciousness like a transistor radio, or if its biological processes are supplemented by some sort of soul or spirit. Injuries to the brain, diseases like Alzheimers and dementia, as well as strokes and lesions, can fundamentally change our experience and personality. Changes to the brain not only alter us in the eyes of others, they make us strangers to ourselves.

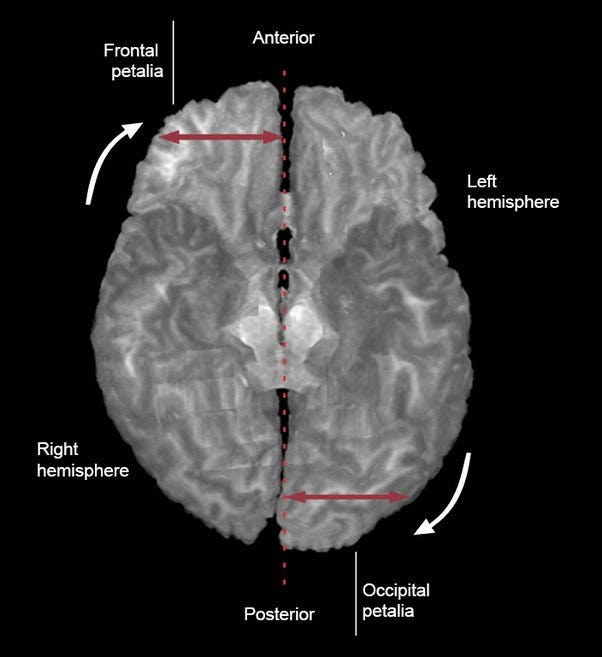

A surprising aspect of our brain is how asymmetrical and lateralized it is. Along with having two hands, two eyes, two legs, two nostrils, and two lungs, we have two distinct sides of our brain: the right hemisphere and the left hemisphere. These two sides are connected by a small, but dense thread of nerves called the corpus callosum.

While talk of being “right-brained” or “left-brained” has long been part of folk psychology, I had always assumed that this was either just an expression, or pseudoscience. That was until I read two recent books by Iain McGilchrist: The Master and His Emissary and The Matter with Things. These books argue that the divided nature of the brain is not only real (although, the left/right differences are not at all what most people think they are), but crucial for the creation and character of our conscious experience.

The Structure Of The Brain

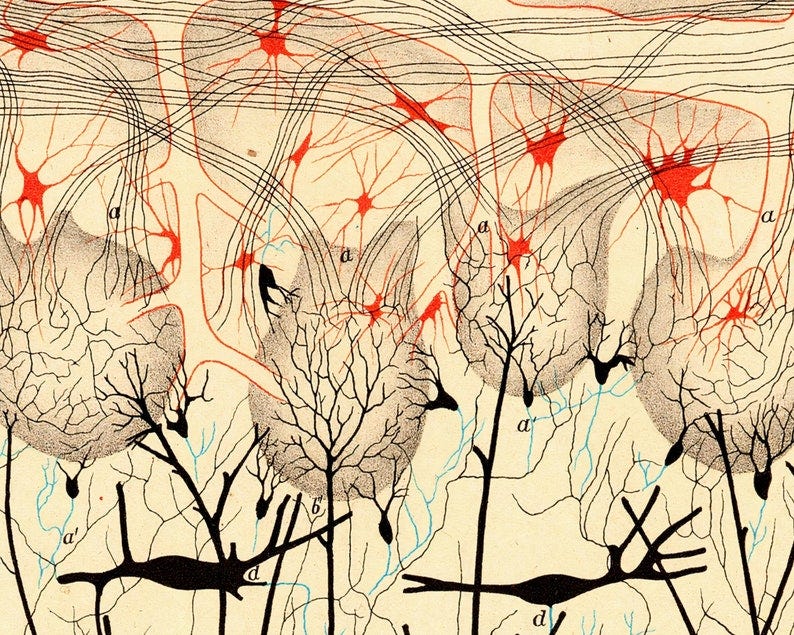

The human brain has over 100 billion neurons and more than 100 trillion synaptic connections. All the work that the brain does is done through synaptic connections. Indeed, the entire purpose of the brain is to connect and send signals across regions—so why would there be a huge separation down the middle? In every creature known to science which has an identifiable brain, the brain is split in half. Also interesting is that the larger the animal’s brain, the smaller (proportionately) the connection is between the two sides. Further, the primary function of this connection is to allow one side of the brain to tell the other side of the brain not to do something, not to collaborate with the other side.

In humans only 2% of neurones in either hemisphere have fibres that cross the corpus callosum, so there is already considerable functional independence. Additionally while the majority of fibres that cross are in themselves facilitatory (employing the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate), many of these connect with interneurones which employ the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (or GABA, for short), so that their overall effect is to inhibit.

As animals get larger and more complex, the two sides of the brain also become more asymmetrical. In humans, the left hemisphere alone is responsible for speech (this is true of many other animals too—the left hemisphere of songbirds actually expands during mating season, and then shrinks again once the mating season is over and complex calls are less necessary) and it is dominant in language comprehension.

The hemispheres differ in size, weight, shape, sulcal-gyral pattern (the convolutions on the cortical surface), neuronal number, cytoarchitecture (the structure at the cellular level), neuronal cell size, dendritic tree features, grey to white matter ratio, response to neuroendocrine hormones and degree of reliance on different neurotransmitters.”

But the differences between the hemispheres are much more profound than this. These differences can be studied through examining the behavior of patients with brain lesions, strokes, or injuries which have affected only one side of the brain. Researchers can also use the Wada procedure, which temporarily anaesthetises one half of the brain at a time, to study each side’s behavior. But perhaps the most revealing studies involve patients who have undergone a callosotomy, a now largely-outdated procedure which severs the connection between the two hemispheres in order to treat severe forms of epilepsy.

These “split-brain” patients now have two independently-functioning hemispheres. As can be seen in the video above, when a picture (say, of a telephone) is shown to the patient’s left eye (which goes only to the brain’s right hemisphere) the left hemisphere has no idea what the right brain has been shown. Because speech is a function of the left hemisphere only, the patient has a feeling that he knows what he saw, but he cannot verbalize it. However, his left hand (which is directed by the right brain) can draw a picture of what it has seen.

It is little exaggeration to say that these patients have two minds. Not only do their hemispheres work independently, they often work at cross-purposes. One man, after undergoing the procedure, found himself “going to embrace his wife with one arm and pushing her away with the other.” In another case, “On several occasions while driving, the left hand reached up and grabbed the steering wheel from the right hand. The problem was persistent and severe enough that she had to give up driving. She reported instances in which the left hand closed doors the right hand had opened, unfolded sheets the right had folded, snatched money the right had offered to a store cashier, and disrupted her reading by turning pages and closing books.”

Watching these experiments can create an uncanny, unnerving effect. It is like we have many conscious agents inside us, and there is no way of knowing whether the ‘unified whole’ we identify ourselves as is really in control. Perhaps there is even another being inside of us which thinks that it is the one which is conscious. As Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Roger Sperry put it:

Each hemisphere [in commissurotomy patients] can be shown to experience its own private sensations, percepts, thoughts, and memories that are “inaccessible to awareness in the other hemisphere. Introspective verbal accounts from the vocal left hemisphere report a striking lack of awareness in this hemisphere for mental functions that have just been performed immediately before in the right hemisphere. In this respect each surgically disconnected hemisphere appears to have a mind of its own, but each cut off from, and oblivious to, conscious events in the partner hemisphere.

The Right and the Left Hemisphere’s Worlds

There is certainly a lot of overlap and redundancy between the right and left hemispheres. So much so that patients can not only survive with just one hemisphere, they can live fairly normal lives. However, as McGilchrist explains, the important differences between the hemispheres lays not in what they do, but in how they do it.

The right hemisphere attends to the world, and makes sense of it, through an experience of the gestalt (“the form of a whole that cannot be reduced to parts without the loss of something essential to its nature”). Split-brain patients, if shown paintings of faces made from fruits and vegetables with their right eye (left brain) will experience the painting as of a pile of fruits. If they are shown the same painting with their left eye (right brain) they will see it as depicting a face. When asked to draw an elephant, patients with serious right-hemisphere damage (who thereby rely on their left hemisphere) will draw “only a tail, a trunk and an ear” and have difficulty arranging the parts into a coherent whole.

In humans, just as in animals and birds, it turns out that each hemisphere attends to the world in a different way – and the ways are consistent. The right hemisphere underwrites breadth and flexibility of attention, where the left hemisphere brings to bear focussed attention. This has the related consequence that the right hemisphere sees “things whole, and in their context, where the left hemisphere sees things abstracted from context, and broken into parts, from which it then reconstructs a ‘whole’: something very different.

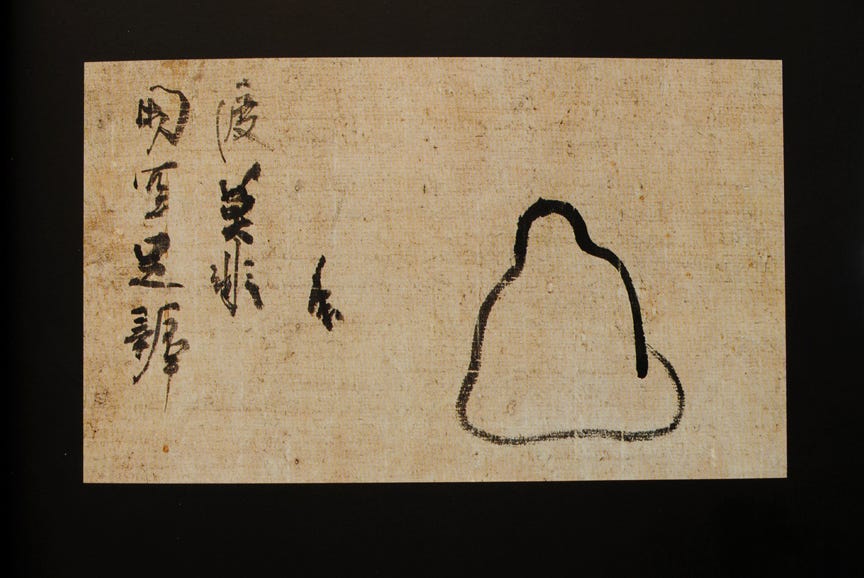

In smaller vertebrates such as frogs, the right hemisphere takes on the role of looking for predators, while the left hemisphere searches for prey. The analogue for this in humans is that the right hemisphere focuses on perceiving the world in a broad holistic way, while the left hemisphere is more narrowly focused on manipulating it. The left hemisphere specializes in tool use, and creating a consistent internal model of the world; the right hemisphere experiences essences which cannot be readily reduced to their parts. While the left hemisphere is in command of language as a system of signs, tokens, and representations, it is the right hemisphere which ‘gets’ jokes, the moral of a story, and poetic metaphors.

The left hemisphere can only re-present; but the right hemisphere, for its part, can only give again what ‘presences’. This is close to the core of what differentiates the hemispheres.

The right hemisphere represents objects as having volume and depth in space, as they are experienced; the left hemisphere tends to represent the visual world schematically, abstractly, geometrically, with a lack of realistic detail, and even in one plane.

Using fMRI scans, we can see that thoughts often start on the right side of the brain, and then pass over to the left to be translated into something which is more sensible and capable of being expressed through language. Expressive hand gestures, particularly the gestures of the left hand, however, are predominately controlled by the right brain. This may explain why people make frantic gestures when they are struggling to put an idea or feeling they have into words.

The right hemisphere specializes in perceiving emotions and understanding the nature of living things. Even left-handed mothers (including mothers who are chimpanzees or gorillas) tend to cradle their infants to the left, which gives their left eye (right brain) a better look at their infant’s emotions. The right hemisphere alone appears capable of reading fine emotional changes in people’s eyes, while the left hemisphere is dependent on looking at people’s mouths. People with severe right-hemisphere disorders may stop being able to see body parts as living, holistic, and individual entities at all.

The left hemisphere appears to see the body as an assemblage of parts…If the right hemisphere is not functioning properly, the left hemisphere may actually deny having anything to do with a body part that does not seem to be working according to the left hemisphere's instructions. Patients will report that the hand ‘doesn't belong to me’ or even that it belongs to the person in the next bed, or speak of it as if made of plastic. One patient complained that there was a dead hand in his bed. A male patient thought the arm must belong to a woman in bed with him.

But with certain right-hemisphere deficits, the capacity for seeing the whole is lost, and subjects start to believe they are dealing with different people. They may develop the belief that a person they know very well is actually being ‘re-presented’ by an impostor, a condition known, after its first describer, as Capgras syndrome. Small perceptual changes seem to suggest a wholly different entity, not just a new bit of information that needs to be integrated into the whole: the significance of the part, in this sense, outweighs the pull of the whole.

Drawing by Emily McClellan. https://www.emilymcclellan.net

McGilchrist believes that contemporary society has reified the left brain’s worldview. It increasingly treats the world as something to be manipulated and controlled, rather than something to be in awe of. It tries to grasp the world as something static and schematic, rather than something filled with flux and meaning. Modern science has shown how the world and humans are like machines, and taught that knowledge consists of breaking things into parts and then seeing how they can be put together again.

The problem is that the very brain mechanisms which succeed in simplifying the world so as to subject it to our control militate against a true understanding of it. Meanwhile, compounding the problem, we take the success we have in manipulating it as proof that we understand it. But that is a logical error: to exert power over something requires us only to know what happens when we pull the levers, press the button, or utter the spell.

But how can we explain and understand the right hemisphere’s umwelt in a serious way? Is it possible to express in language something which is mute? Can we represent the part of ourselves which exists prior to representation? To do so, we will need to turn to, in my opinion, the greatest cartographer of the right hemisphere’s world—Martin Heidegger.

After his talk at the How The Light Gets In festival in Wales, I brought up to McGilchrist that much of what he was saying about the right hemisphere had already been described by Heidegger. McGilchrist understood my point, but thought that Max Scheler’s worldview was a more accurate analogue of the right brain’s world. I went back and reread some of Scheler’s work, but I respectfully disagree with McGilchrist. I will explain why in the next section.

Heidegger and the Destruction of Western Philosophy

The modern philosophical tradition has tried to think of the human being (referred to in philosophical lingo as “the subject”) as abstracted from, and standing apart from, the world. This has been the case particularly since Descartes and Kant, who stressed that the mind is radically separated from the external world, to the point where it is impossible to know with certainty what goes on outside of our minds. Descartes famously reduced all that could be known with complete certainty to “Cogito Ergo Sum” (“I think therefore I am”).

Descartes and Kant claimed that while the subject is radically separated from the world, it can use thought and a priori knowledge to make representations of the external world which help the subject act upon the world in ways that work—that produce predictable effects. For Heidegger, this presents the world to us “with its skin off.”

Heidegger believes that philosophy since the cogito ergo sum has focused far too much on the ‘think’ part of the equation and nearly enough on the ‘am’—what it means to be. Indeed, Heidegger begins Being and Time with the lamentation that ‘today the question of Being has been forgotten.’ For Heidegger, Descartes’ philosophy is flawed in that it takes thinking as what is most basic to the human being, and not the more fundamental—and more expansive—state of ‘being.’ Heidegger emphasizes that without being embedded in some meaningful context, philosophy or thinking, is not possible at all.

Particularly through the right brain, we often comprehend things through their meaning (like understanding the meaning of a poem), it affects us, it is not a matter of logically grasping things. Heidegger says that philosophy, and Descartes in particular, has gotten it wrong by reducing Being to ‘thinking.’

Heidegger as the Revealer of the Right Hemisphere

Heidegger tries to break away from the Western philosophical tradition by inventing his own terminology, which comes without the historical baggage. The terminology—which at first appears as the most annoying and pretentious part of his thought—given time and attention, often becomes the most appreciated aspect of his work. It is what allows us to see the world anew, and escape bad habits of thought. But it does set up a steep learning curve. As Professor Mary Rubenstein explains,

His thinking functions as its own universe, the Heid-a-verse, a self-enclosed holographic system in which everything swirls around the everything else it already presumes. And the whole thing is covered in a thick shell of impregnable syntax. Existence, Heidegger tells use, is “the being of those beings who stand open for the openness of being in which they stand by standing it.” So we read and our eyes glaze and we read more because that didn’t make sense...so maybe this will, but no it won’t...until finally days or months or years later something does make sense! And your exhilaration collides with total despair as you realize you’re trapped inside the very holographic Heid-a-verse you’ve spent so long locked out of—and how did you get in? And where is the door? Now it makes sense, you can say it in his language, and you feel somehow that you get it, but you can’t translate it because everything requires everything else.

Heidegger begins his study by explaining that it will be an investigation into the nature of Being. This investigation will be different than the type one could read in a science textbook, because Being cannot be described by its factual characteristics—it cannot be measured, or weighed, or broken into smaller pieces. It doesn’t have properties like “red,” “large,” or “cold.” Being is that which allows entities to have these and other properties, but it is not an entity in itself. As Heidegger explains: “‘Being’ cannot be derived from higher concepts by definition, nor can it be presented through lower ones...we can infer only that ‘Being’ cannot have the character of an entity.”

The human being, which Heidegger terms ‘Dasein’ is a special mode of Being. It is special in that Being is an ‘issue’ for it. Dasein is different from other entities (such as tables, chairs, or fruits) in that it is capable of experiencing and questioning its own Being.

Also fundamental to Dasein is that it exists in time. Dasein’s time is finite—it is a being-towards-death, a Being that will inevitably become a non-being. Time is that which allows Dasein to have possibilities and that which allows it to move through the world. In Heidegger-ese: “We shall point to temporality as the meaning of the Being of that entity which we call ‘Dasein.’ Time needs to be explicated primordially as the horizon for the understanding of Being, and in terms of temporality as the Being of Dasein, which understands Being.”

While English translations of Dasein are contested and somewhat counterproductive, two prominent examples include ‘being there’ and ‘the having-to-be-open.’ This ‘being open’ suggests that Dasein is always entangled in, and inseparable from, other entities. While the subject of Kant and Descartes stands apart from or over the world, Heidegger wishes to show us Dasein in its ‘everydayness’—getting water, speaking with others, playing instruments, waiting for the bus.

The fundamental everyday nature of Dasein is that it exists within, and consists of, a world. But Dasein is not in the world in the same way in which water is in a glass, or a table is in the room. Dasein dwells in the world, it doesn’t just exist in it. The world, or the sense of the worldhood-of-the-world is the totality of Dasein’s involvements.

The filmmaker Terrence Malick was a doctoral student specializing in and translating Heidegger, before he transitioned to making movies. His films use wider lenses with a deeper focus to situate characters within an environment, to merge the characters’ feelings with the external world. He also only uses natural lighting so that his actors can move through the environment in a more free, improvisational manner. Mallick has attempted to “compose in depth” to make his films feel alive and three-dimensional in a way that encircles you—it is an attempt to capture the feeling of Being. Mallick’s works were incredibly influential for Chloe Zhao’s recent Best Picture Winner, Nomadland.

Heidegger identifies two modalities in which Dasein encounters objects in the world: as present-at-hand and as ready-at-hand. When an object is present-at-hand, we are encountering it outside of its context, we are looking at it, thinking about it, or even studying it, but we are not fully engaged and wrapped up in it. Maybe we have measured it, or collected certain facts about it, but we are not using it in a way which illuminates much about ourselves or the object.

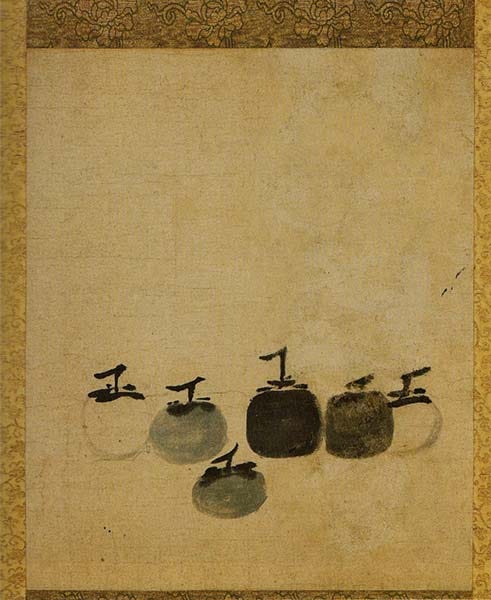

Equipment is ‘ready-at-hand’ when we are using it in such a way that it is difficult to draw a distinction between our Being and the Being of the object. The basketball is ready-at-hand when Michael Jordan is dribbling it, the marble is ready-at-hand when Michelangelo is sculpting it. Heidegger’s classic example of ready-at-hand is that of a master carpenter hammering. When in the act of using the hammer, its meaning and nature are transparent without the carpenter even needing to think about it. This is a right-brain apprehending of the hammer, not the making of a left-brain representation of the hammer. If the hammer breaks, only then does it become unready-at-hand, it loses the flow which binds the hammer to the rest of the carpenter’s world. If the hammer is no longer treated as equipment, but as a mere object, it becomes present-at-hand.

…The less we just stare at the hammer-Thing, and the more we seize hold of it and use it, the more primordial does our relationship to it become, and the more unveiledly is it encountered as that which it is-as equipment. The hammering itself uncovers the specific 'manipulability' of the hammer-Thing, and the more we seize hold of it and use it, the more primordial does our relationship to it become, and the more unveiledly is it encountered as that which it is-as equipment.

The kind of Being which equipment possesses-in which it manifests itself in its own right-we call "readiness to-hand.” Only because equipment has this 'Being-in itself' and does not merely occur, is it manipulable in the broadest sense and at our disposal. No matter how sharply we just look at the 'outward appearance'" of Things in whatever form this takes, we cannot discover anything ready-to-hand. If we look at Things just 'theoretically', we can get along without understanding readiness-to-hand. But when we deal with them by using them and manipulating them, this activity is not a blind one; it has its own kind of sight, by which our manipulation is guided and from which it acquires its specific Thingly character.

At this point we may be tempted to stop and ask ourselves ‘is any of this true?’ But that would reflect that we’re still stuck in the Descartes/Kantian/left-brain worldview. For Descartes and Kant, the problem is that we are stuck in our own minds and separate from the world, so it becomes impossible to know the world definitively. The best we can do is try to grasp the external world in a way which logically coheres with our idea of it. But for Heidegger, we are the world, the world discloses itself, makes itself known to us. In the words of my old professor Peter Steinberger: “Again, Heidegger seems to think that the problem of Mind and World is a non-sense problem, skepticism is a non-issue, neither right nor wrong but unintelligible, Dasein is Being-in-the-World so it makes no sense even to think about there not being a world. We don’t really get a refutation of skepticism; rather, skepticism is just noise.” For Heidegger, meaning and significance is intrinsic to the nature of Dasein’s entanglement with the world.

In interpreting, we do not, so to speak, throw a 'signification' over some naked thing which is present-at-hand, we do not stick a value on it; but when something within-the-world is encountered as such, the thing in question already has an involvement which is disclosed in our understanding of the world, and this involvement is one which gets laid out by the interpretation.

This synergizes well with McGilchrist’s depiction of how the right brain sees the world:

Truth is uncertain not because it is empty, but because it is full – rich, complex, manifold. (This is related to what I believe to be the mistaken assumption that because we cannot pin down the ‘meaning’ of the world in which we live, it has no meaning: I will argue that this experience comes not from there being no meaning, but from there being a plenitude of meaning, beyond simple articulation.)

Perhaps McGilchrist would also support the notion that the left brain’s job is to make explicit, make present-at-hand, what is already experienced as ready-at-hand by the right brain.

The Nature of Being Consists of Authenticity and Inauthenticity

As previously mentioned, Dasein’s existence is one both of possibilities and a relentless Being-towards-death. For Dasein, death is not just an abstract concept which will happen to it someday in the future; death is what makes its possibilities and time finite, and thereby meaningful. Death produces an anxiety in Dasein which makes Dasein know that it must strive to achieve itself.

Most of the time, Heidegger argues, Dasein is not living authentically—it is not achieving what is its own-most Being, it is not living with a true alertness that it will die. Most of the time, Dasein ‘falls into inauthenticity’ through superficial chatter and gossip, constantly seeking new entertainments and stimulation (rather than dwelling), and listening to the ‘They.’ The They is what Heidegger terms the indeterminate mass of people who pass judgement on one’s activities—they say you need to go to college, they think you shouldn’t dress like that, they think your art doesn’t make sense. The They is what distracts, and discourages Dasein from achieving its own-most being and understanding that it will die.

In the publicness with which we are with one another in our everyday manner, death is 'known' as a mishap which is constantly occurring-as a 'case of death'. Someone or other 'dies', be he neighbour or stranger. People who are no acquaintances of ours are 'dying' daily and hourly. 'Death' is encountered as a well-known event occurring within-the-world. As such it remains in the inconspicuousness characteristic of what is encountered in an everyday fashion. The "they" has already stowed away an interpretation for this event. It talks of it in a 'fugitive' manner, either expressly or else in a way which is mostly inhibited, as if to say, "One of these days one will die too, in the end; but right now it has nothing to do with us."

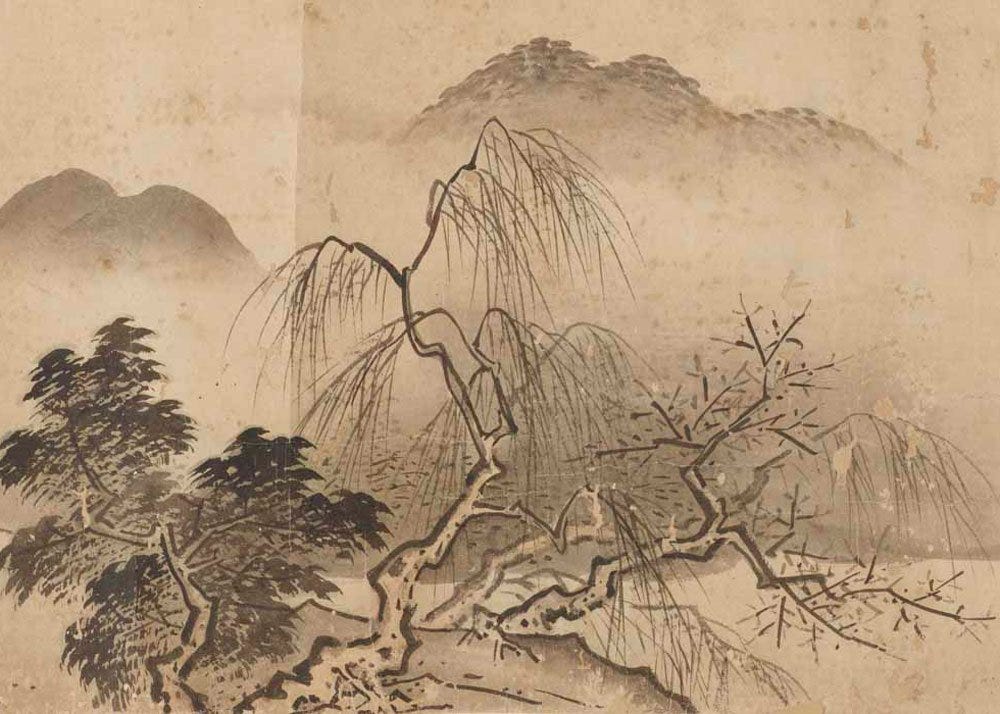

Heidegger also believes that modern technology and the modern relationship to nature threatens the ability of Dasein to live authentically. In premodern times, Heidegger writes in The Question Concerning Technology, artisans and craftspeople worked with the inherent qualities of their materials. There was a mutual understanding between the artist and their medium.

If he is to become a true cabinetmaker, he makes himself answer and respond above all to the different kinds of wood and to the shapes slumbering within wood—to wood as it enters into man's dwelling with all the hidden riches of its essence.

The true artist engages in a ‘poetic habitation’ with their materials, which thereby reveal themselves to us as objects of respect and wonder. The artist and craftsperson’s job is to bring forth and disclose the hidden essence of the materials. The artist brings forth the full meaning of the materials, which helps us engage authentically with them. By contrast, modern technology engages with materials by challenging forth—it ignores the inherent qualities of materials and compels them to become nothing but resources to be collected and stored. Following this, if the poetic nature of the material is not disclosed, it becomes something to be used up and thrown away. It’s not difficult to see that this is left-brain instrumentalist thinking run amuck.

In contrast, a tract of land is challenged in the hauling out of coal and ore. The earth now reveals itself as a coal mining district, the soil as a mineral deposit. The field that the peasant formerly cultivated and set in order appears differently than it did when to set in order still meant to take care of and maintain. The work of the peasant does not challenge the soil of the field.

Interviewer: But someone might object very naively, what must be mastered in this case? Everything is functioning, more and more electric power companies are being built, production is up, in highly technologized parts of the earth, people are well cared for, we are living in a state of prosperity, what really is lacking to us?

Heidegger: Everything is functioning. That is precisely what is terrifying, that everything functions, that the functioning propels everything more and more toward further functioning, and that technicity increasingly dislodges man and uproots him from the earth. We do not need atomic bombs at all to uproot us. The uprooting of man is already here. All our relationships have become merely technical ones. It is no longer upon an earth that man lives today.

How The World Discloses Itself to Babies

We have now dived into the meaning of Dasein in its everydayness, and in its being-towards-death. Now, I would like to add a short(ish) post-script on those qualities that Dasein is endowed with at birth. According to Heidegger, Dasein is ‘thrown’ into the world, Dasein is always subject to an ‘already-having-found-oneself-there-ness’. There is no Dasein present before it finds itself thrown into the warp and weft of its involvements.

Riders on the storm

Riders on the storm

Into this house, we're born

Into this world, we're thrown

Like a dog without a bone

An actor out on loan

Riders on the storm—The Doors, Riders on the Storm

Recent neuroscience has uncovered some interesting findings on how the Baby Dasein stands open to the world. Elizabeth Spelke’s recent book, What Babies Know (which has not received the recognition that it deserves as a philosophical landmark) has argued that babies are born with certain faculties—a set of ‘core knowledge’ systems—which makes the world intelligible to them. Spelke’s investigation uses the left-brain language of science, and is not an ontological study like Heidegger’s Being and Time. However, I do believe that her findings can help shed light on what is most primordial about Dasein’s Being.

Spelke and her collaborators’ research examines how babies navigate their environments, compares the feelings of surprise indicated by babies’ eye movements and facial features when exposed to certain (sensical and non-sensical) situations, studies how animals raised in controlled conditions navigate environments, and more. Decades of research have led Spelke to identify six innate core knowledge systems: “Infants’ learning rests on a set of cognitive systems that we share with animals and that evolved over hundreds of millions of years. At least six distinct systems serve to represent highly abstract properties of the unchanging navigable environment, of movable objects, of number, and of the living, animate, and social beings who populate our world.” These innate systems are then used by adults to create more complex and sophisticated forms of knowledge.

The object core knowledge system allows sighted babies to know that objects persist over time, how far away from the baby they are, that objects typically slow down unless acted upon by gravity or another external force, and that objects which collide with other objects may stop, or cause the other object to move. Babies both understand the difference between small objects and larger objects that are seen from a greater distance, and use how close their pupils move together when they look at an object to judge the object’s distance. While babies do not have good muscle control, they know about how far to reach for an object they want. Young animals raised in complete darkness, and mice who only begin to see six weeks after birth are able to do the same things immediately after taking in their first visual stimuli.

First, inexperienced human infants do not appear to experience a confusion of depthless sensations but a spatially coherent world. Second, infants gain knowledge about the world not only through the shaping effects of their experiences acting on the environment but through processes akin to rational inference: They infer not only the distance of an object from the two directions in which their eyes are pointed inward but also the size, position, and motion of an object from other geometric variables, including the size, shape, or position of the object’s image in the infant’s visual field, and the distance, slant, or motion of the infant relative to the object.

Infants at very young ages also have an intrinsic knowledge system which lets them memorize places and orient themselves within the environment. However, this system operates not at all how one would expect it to.

While babies largely ignore obvious landmarks, they navigate and orient themselves through paying attention to subtle perturbations of the ground surface. Spelke’s lab initially landed on this insight when disoriented Babies failed to use a bright blue wall in a four-sided room of otherwise white walls to find a toy or snack. However, babies were able to find the snack using small topographical features of the floor.

Spelke has hypothesized that babies use this ancient system, which she posits evolved long before humans, because it 1. Prevents false positives of babies thinking that two places are the same place 2. Prevents babies from thinking that a familiar place is a new place because furniture, plants, or objects have moved places 3. Does not overload the baby with distracting or useless information.

These findings provide evidence that young children determine their sense of place only in relation to the ground surface on which they navigate: They do not use properties of the walls or the ceiling of the room to guide their reorientation, except insofar as the walls intersect the floor. When the ground turns upward, either at the wall of a room or at a bump or ridge on the floor, that turn enters into a child’s spontaneous representation of where she is in her surroundings.

There are striking limits to the features of the environment that children and animals use to recover their sense of place when they are disoriented. Toddlers, chicks, and zebrafish reorient only by features of the continuous ground surface, including subtle bumps on the floor of a room or tank, and not by large, freestanding objects. Where the ground surface is bounded by walls or perturbed by bumps, children reorient by differences in the distances and directions of these perturbations but not by differences in their lengths or corner angles.

Another crucial core knowledge system allows babies to understand and anticipate the behavior of other agents. Very young infants do not expect agents to interact with objects that they cannot see or hear (because they are hiding behind a wall), and infants expect agents to interact with objects which they have previously found valuable or useful. For example, if an agent sees both a blue toy and a red toy, and they travel a greater distance for the red toy, babies will be very surprised and confused if the agent goes for the blue toy when both toys are placed at an equal distance from them.

Infants are also remarkably good at memorizing faces. However, infants are equally good at distinguishing the faces of individual humans, chimpanzees, sheep, and other animals—it is only later on that infants specialize in recognizing humans, and lose much of their ability to tell individual animals apart (this further gives credence to Spelke’s idea that these core systems are ancient, evolving long before humans).

In summary, 3-month-old infants, who cannot pick up objects and manipulate them, nevertheless expect the actions of agents who have these abilities to be efficient and causally efficacious... At 3 months [at the latest], infants reason about people’s actions by drawing on abstract, interconnected concepts of causal efficacy, efficiency, goal-directness, and perceptual access.

These, and other core systems, show us how the world initially discloses itself to Dasein. The world does not start as a place of completely foreign and unpredictable phenomena which must gradually be learned. From our moment of ‘thrownness’ into it, it is a world of agents, physical laws, distance and depth, sociality, and location.

But do these findings truly match Heidegger’s view of the world? In some ways yes—it is likely that the baby instantly feels involved with the world, it doesn’t need to slowly strive to logically grasp it in order to function. But the knowledge which Spelke has identified is also incredibly abstract, often almost mathematical seeming, it is one of distance and measurements, not merely emotion and meaning. Spelke claims that her studies have began to “overturn the traditional view that human knowledge begins with specific sensory-motor experiences and arrives at abstract concepts only at its pinnacle.” So…Is the baby dominated by the right or the left brain? Currently the science says the answer is neither. McGilchrist cites evidence that infants and young children have a far greater balance between the hemispheres than adults:

Pre-adolescent children find it relatively difficult to use their hemispheres separately, which is still further evidence of the inhibitory role played by the corpus callosum in adults. Interhemispheric connectivity grows during childhood and adolescence, with the result that the hemispheres become more independent.

Is a balance between the hemispheres throughout life possible? Will the left hemisphere inevitably win out with the expansion of modern philosophy and technology? An upcoming Hidden Threads will seek to give the left hemisphere its due, and show how its faculty of language has played a unique role in separating humanity from animals.

So incredibly interesting!!!! Superb writing!